Carl Zimmerman’s Niagara Hydro Power Station

In 1997, Carl Zimmerman first exhibited a suite of sepia and cyan-toned photographs entitled Lost Hamilton Landmarks. These photos were presented as if they were documentation of Hamilton, Ontario’s industrial and institutional architecture that had been torn down.

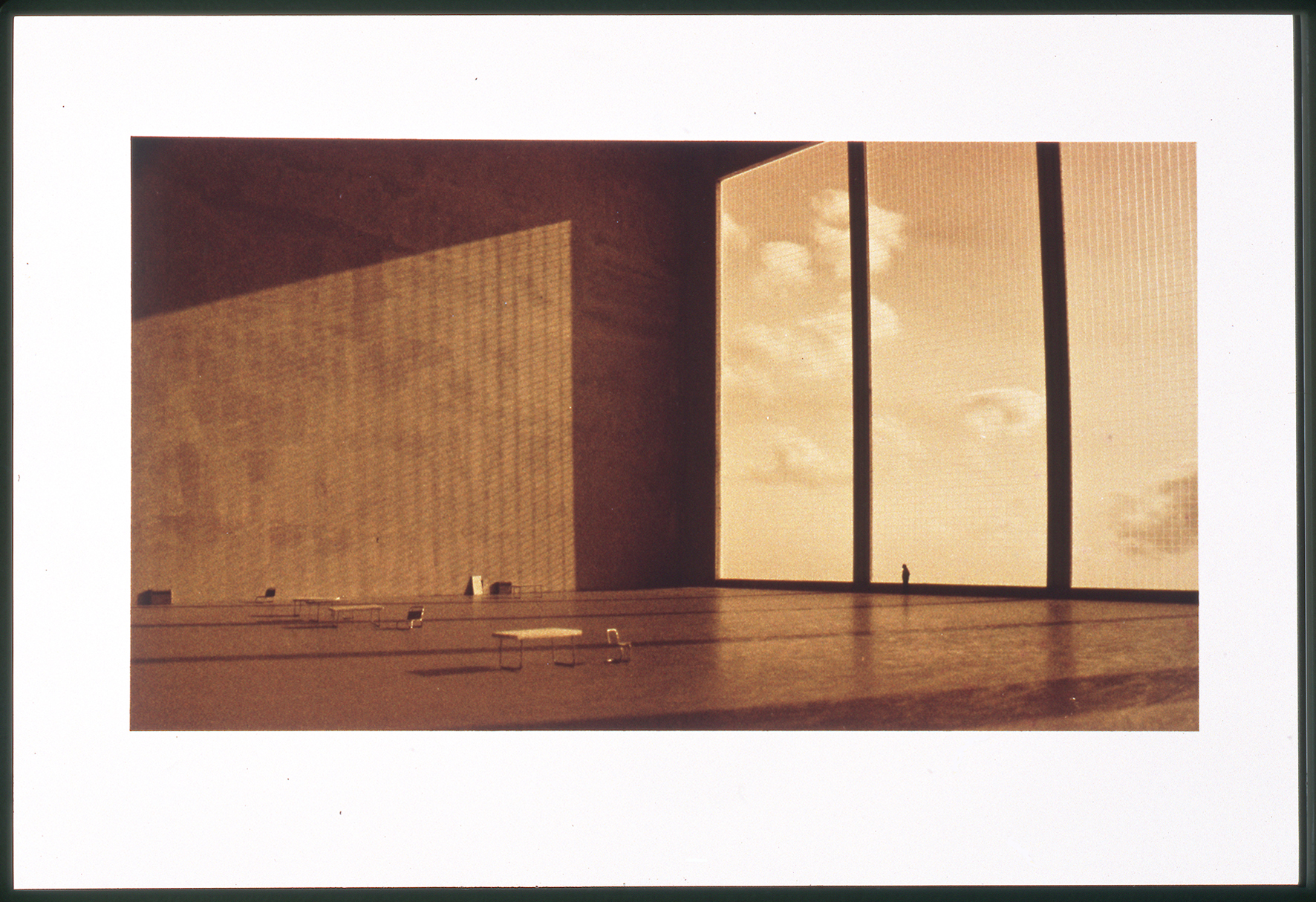

In Niagara Power Station, a lone figure in silhouette occupies a room as vast as an aircraft hangar. An entire wall is paned glass that is at least twenty times taller than the individual. A low sun casts the shadow of the windowpane grid across the concrete wall and floor. What appears to be Marcel Breuer modern steel chairs and tables are strewn about the space. This furniture is shorthand for twentieth century modernist idealism. Lightweight, airy, chrome furniture suggested a future made better by technological and industrial innovation. The title, Niagara Power Station, speaks of the industrial revolution that took place in the Hamilton region with the advent of electricity. There are only a few pieces of furniture, sparsely spaced and randomly strewn across the dusty floor. The implication is that this power station is abandoned and to a larger extent, something has failed or changed.

The scene Zimmerman presents is one of utopian idealism exhausted and redundant. A student of Canadian architectural history would deduce that this space and the others in Lost Hamilton Landmarks never existed. They are too absurdly massive to not be widely known. They have the scale and pared-down classicism of totalitarian architecture. If the series were called Lost Berlin Landmarks the viewer would not be naïve to accept these photographs as factual. The buildings have the scale of Albert Speers plans for the new Berlin the Nazis dreamed of building. Is Zimmerman positing an alternative history of Hamilton where these landmark structures were built and later destroyed? The absurd scale of these spaces (try heating them during a Canadian winter) points to the subtle humour lurking in his work.

All of the works in Lost Hamilton Landmarks are shot from a low angle. This makes the spaces seem cathedral-like and the viewer feels like they would be overwhelmed by the space. Carl Zimmerman was born and grew up in Hamilton, Ontario before moving to Nova Scotia in 1974. The Hamilton he grew-up in was nicknamed “Steeltown” for its main product. While living in rural Nova Scotia, Zimmerman was reimagining the industrial city of his childhood with its enormous steel mills and factories. The low angle of the camera in this series of works is like a child’s point of view. When we revisit spaces vividly remembered from childhood, we are often taken aback at how much smaller they are than we remembered.

These are photographs of detailed models that the artist constructed and photographed in natural light with a 35mm SLR film camera. Our familiarity with the effects of natural light helps convince us that we are seeing something real. We are looking at photographs, but Zimmerman’s greatest skills went into the making of these models. Furniture was hand-made with wire and surfaces were painted to appear aged and weather beaten. His skill set is that of the film model maker. In Niagara Hydro Power Station, the wall of paned glass is in fact Plexiglas, that had been scored with a knife. As with film sets, all the work is about creating a convincing image within the camera frame. These works are pre-digital in technique which is apt as they are recalling the past and evoking memories of a time before computers. We live in the era of the Deep Fake where no image can be trusted completely. Zimmerman’s Lost Hamilton Landmarks presages our current unease with media and its relationship to truth. Niagara Hydro Power Plant is an analog, plywood and paint, deep fake of Hamilton’s past.