THE PATH WE SHARE

Artist Alan Syliboy’s Vision for a Powerful First Nations Residency

On Friday, February 5, the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia’s space known as the Zwicker Gallery—the one with the tall ceilings, beautiful wood floors and spiral staircase—is a flurry of activity. Arriving breathless, I step around cordoned-off areas and squeeze by the various groups of people working on final preparations for the opening of a special new exhibition, The Path We Share(Ne’wtejk Witawti’minuk in Mi’kmaq), to get to the center of the space to try and locate my interview subject. I stop for a few moments and watch as the curatorial staff smooth out the exhibition title letters onto the wall. I look up to see a staff member perched at the top of a mini crane-like vehicle as he tends to a very large work comprised of four banners. I eventually look down to see some unique-looking installation works placed directly onto the floor, making a mental note to carefully maneuver around to avoid walking into them. Eventually my eyes rest on a man at the bottom steps of the big staircase, somehow looking calm and composed in the midst of it all: there sits Alan Syliboy (BFA, NSCAD), renowned and highly respected Mi’kmaq artist, patiently waiting for me and our scheduled chat.

Borne of two creative residencies with four First Nations artists, The Path We Share is the result of Alan Syliboy’s brain child, which would include two collaborative exchanges in Nova Scotia—one at The Deanery Project in Lower Ship Harbour in 2014, the other on Brier Island and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia’s Yarmouth location in 2015 (with additional discussions and communications adding to the process when the group was apart). Through a unique process of self-directed dialogue and artmaking, the foursome focused on reconciling the parallel journeys of the Mi’kmaq People and the whales of the North Atlantic. The result? A very rich, complex and beautiful collection of mixed media works, including sculptures, drawings, film, photographs and more, all focused on shared stories of contact and consequence, with an aim to arrive at newfound forms of expression and understanding.

When I met earlier in the week with David Diviney, the show’s curator and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia’s Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, I asked him for his thoughts from an institutional point of view: “The Gallery was focused on facilitating this truly special, artist-led approach by providing a platform for the artists and the community to work from,” said Diviney. “The residency makes visible a creative process that visitors aren’t usually privy to when viewing an exhibition. This meaningful approach, which saw the artists travel on water to get closer to the whales, has created what should be an invaluable experience for visitors, the community and the Gallery itself.”

It occurred to me that we were a coastal people once, but we aren’t now—over time the connection was lost, and I wanted to reclaim that. I wanted to reclaim the connection to the sea.

Flashing back to opening day, Syliboy and I settle into a nearby gallery space and start by broaching the general theme of whales and reconciliation—first proposed by the artist and unofficially led by him throughout—and what it represents to him personally. Was it a deep-rooted conceptual project that had been percolating for years? Or did it develop in a more natural, organic way? “I think I just realized a few years ago that my works didn’t include images or themes of dolphins or whales. Then it occurred to me that we were a ‘coastal’ people once, but we aren’t now—over time the connection was lost, and I wanted to reclaim that. I wanted to reclaim the connection to the sea.”

Syliboy then explains that from this simple but powerful realization grew a search to find other First Nations artists who might be interested and available in collaborating with him on the idea. After some personal outreach, he was thrilled to enlist artists Charles Doucette, Fran Francis and Courtney M. Leonard, each with different approaches who use a variety of mixed media, and who wholeheartedly agreed to embark on a journey—mostly: “Well, Frannie [Fran Francis] did have reservations at first because of her fear of deep water. But eventually she realized that she might need this for herself, that she might be able to confront that fear through the whales, and she was drawn to that. It’s amazing that she was able to join us on this.” Francis (BA Fine Arts, Saskatchewan Indian Federated College), also a Mi’kmaq artist who works primarily in visual and textual media, contributed the impressive larger-scale panels (mentioned earlier) to the exhibition.

Fran Francis, Crying in the Deep, 2015-16, Acrylic and beading on canvas, qty. 4 panels ea.

I ask Syliboy—born and raised in Truro, and living in the Millbrook First Nations community—about his own connection to the theme. “As a child, I spent some time with my Step-Father in Pictou [Nova Scotia] right on the water, and the kids there spoke only Mi’kmaq,” he recalls. “That’s where my love of the sea started, a long time ago.” Later on, Syliboy began a private study in 1971 with artist and activist Shirley Bear (an Order of Canada recipient), furthering his arts education at the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design (NSCAD) four years later. His accomplishments include the creation of a limited edition Butterfly gold coin for the Canadian Mint in 1999; receiving the Queens Golden Jubilee Medal in 2002; and leading a group of artists who collaborated on a sculpture commissioned for the 2010 Olympics.

Courtney Leonard, Archetype, 2014-16, colour photograph.

When the conversation shifts to contributing artist Courtney M. Leonard (MFA, Rhode Island School of Design)—the only First Nations artist based out of the United States, in Santa Fe—Syliboy’s voice is discernably pleased: “I first met Courtney at a conference in Connecticut 10 years ago, and I’d been wanting to collaborate with her for a while now” he shares. “When I got to know her and her work, I noticed her pottery looked exactly like Mi’kmaq works. While she’s a member of the Shinnecock Nation in the States, our Peoples come from the same confederacy, and we used to have annual get-togethers. They also have a reserve right on the water, and share the same connections to water that we used to.”

Charles Doucette, Travel by Night, 2016, acrylic on wood.

We turn our attention to multimedia artist Charles Doucette (BFA, NSCAD) of the Potlotek First Nation, also a band organizer of a commercial, food and ceremonial fishery. “I’ve known Charles’ work for a long, long time,” Syliboy muses. “I like his work because it’s really thought-provoking. It’s land-based work—he’s outside all the time. He’s a true artist in the sense that he’s making art every single day. Whether someone is there to see it or not, whether it’s recorded or not, he’s always creating something. I like that aspect.”

I bring up my impression that the theme of reconciliation seems to be garnering more attention in the last few weeks and months. Post-elections, the new Federal Government stated, “Our priorities for improving the relationship between Canada and Indigenous Peoples are clear.” And recently, the National Arts Centre in Ottawa started the New Year with presentations of commissioned projects for their dance and orchestra disciplines that centered on the topic of “truth and reconciliation” and the poem I Lost My Talk by Mi’kmaq artist Rita Joe. I wonder aloud if Syliboy has noticed this. “I don’t know… Not really. What’s happening now is just naturally coming to the surface,” he says. He pauses before adding: “It heats up and cools down. It’s just the way it’s always been, for many years, as far as I can tell.” It becomes clear that questions of a broader, more political nature doesn’t seem to be what particularly interests—or drives—the artist at the moment, so we stop there and decide to duck back into the exhibition space to look at the works.

I don’t really stop to be emotional, he says, pausing to think. It’s the process in general that is emotional.

We linger over his intricate drawing, Whale and Star. “This is a throwback to about 10 years ago, when I was at the kitchen table, no studio, just a pen, paint and paper. I started with petroglyphs and everything evolved from there.” He continues: “Here, we have humans watching the whale, and the whale is blowing blood. I think the message here is pretty clear.” I find this particularly affecting and ask—or shout over the cacophony around us—if he ever gets emotional as he’s working on pieces that present difficult subjects. “I don’t really stop to be emotional,” he says, pausing to think. “It’s the process in general that is emotional. In the actual moment, you’re balancing this out here and that there, you’re constructing, and you can’t wait to get to the next line,” he adds, pointing to the actual lines in the work.

Alan Syliboy, Whale and Star, 2016, acrylic and pen on rag paper, 55.88 x 76.20 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

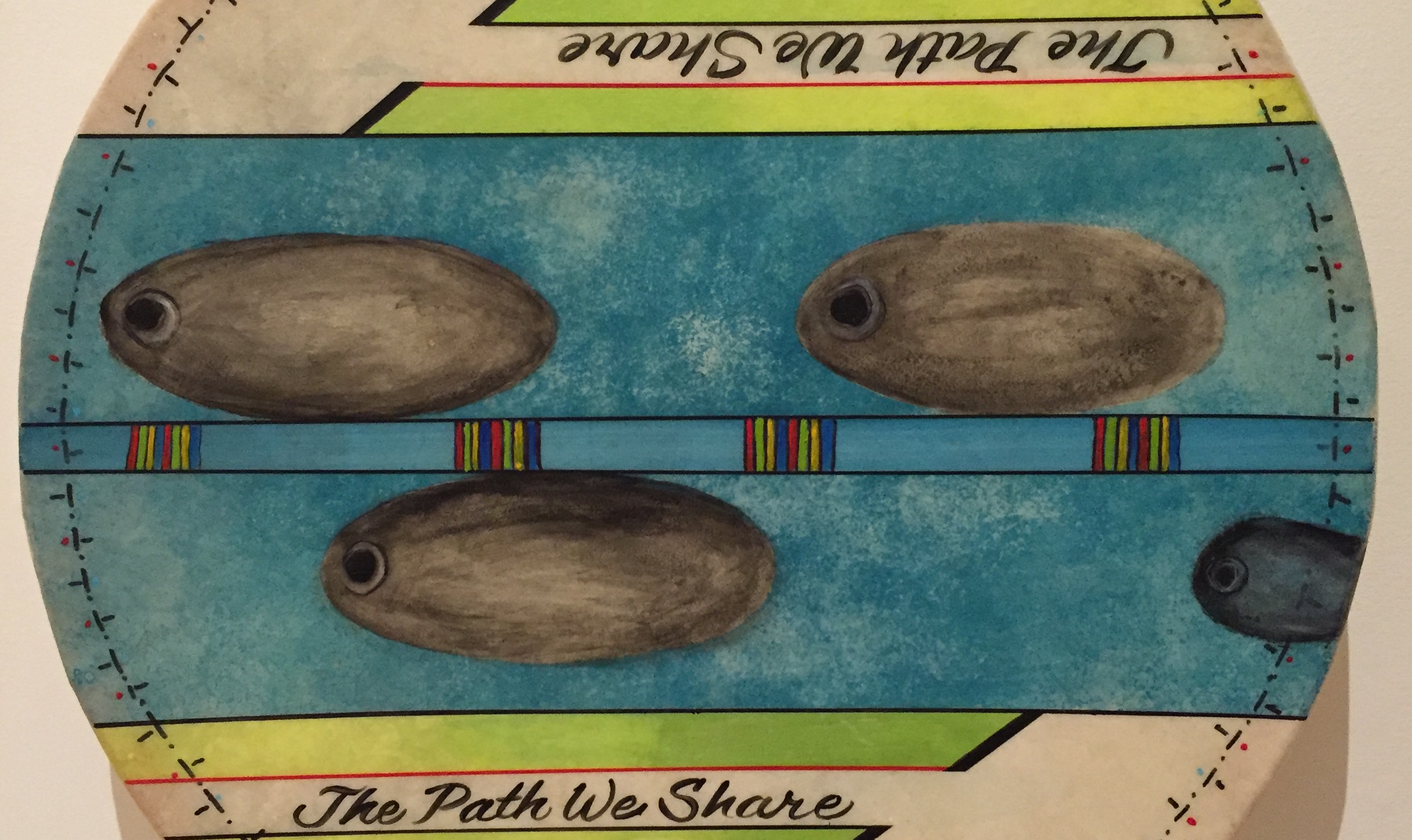

We take time to view nearly every single work in the exhibition, some produced individually, others in collaboration with one another, and finally stop at one of the installation pieces that I’d seen on the floor earlier on, Whale Eyes. “The eyes are a key theme here, because the eyes are what drive interaction for us, and it’s the same for the whales. We are communicating just by looking at one another,” Syliboy says. The artist further explains that the number four appears as a pattern throughout the collaboration, as seen with the depiction of four whales in his and Leonard’s drum work, The Path We Share. He gets a slightly faraway look in his eyes as he recalls the time the group traveled to Brier Island [as part of the residency program] and saw a group of four whales emerge at once as the group of four artists looked on. Filmmaker Nance Ackerman, who is working with the group in documenting the project, captured the moment on film, where Leonard can be seen wiping a tear away (this clip appears in the video on the group’s Kickstarter webpage, which is generating funds towards the completion of the film).

Courtney M. Leonard and Alan Syliboy, The Path We Share, 2016, acrylic and pen on elk skin.

Another video work with audio, also titled The Path We Share, feels especially hard-hitting. Produced in partnership with the Nova Scotia Community College’s Truro campus, it includes a reenactment set in 1936, when the Mi’kmaq used to hunt whales and sell oil harvested from whale parts. Syliboy doesn’t shy away from the message: “Back then, we made the oil and sold it as a way to support ourselves and our communities. But when the big oil companies took over, we had nowhere to sell it anymore.” He elaborates, eyes still on the TV screen: “Think about the scale of it: one single whale, one single animal could be used by a big group of people. That was the sustainable way, as opposed to the industrial and what’s going on now.”

In this world, you don’t see a show like this very often.

As we wind up, I ask for some parting thoughts about the exhibition and the experience visitors can expect. “In this world, you don’t see a show like this very often. Not only will people experience something they probably haven’t before, it also gives hope to new artists, who will see that they can come to a place like the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and see a show like this. That’s really powerful,” he added.

*****

Later that evening at the opening reception—the exhibition now ready to be viewed in all its glory—the artists, Gallery staff, members and other special guests gather for a presentation. The event is well-attended and feels appropriately intimate. Surrounded by the works, the crowd listens as Elder J. Hubert Francis leads a prayer: “We need to acknowledge and give thanks to the Creator for gifts that we all have, that we are all bestowed: really, it’s for the gift of art. These gifts are medicine, not just for the people that look at the art, or listen to the music. It’s medicine for the arts, so that the medicine is spread and shared. We need to give thanks for these medicines we are bestowed.” It’s a visibly special moment for the artists and guests, who are then treated to a poignant Whale Honour Song with drum, shaker, electric guitar, double-bass and voice, which sounds like a bluesy interpretation of traditional First Nations music. Stationed up on the balcony to capture some video footage, I have an opportunity to take in the stirring scene below. Guests, artists, musicians, collaborators and supporters, from various walks of life, all gathered to celebrate an important and unique exhibition full of incredible works by Four Nations artists.

The Path We Share is on view at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia until April 24, 2016

All images in this article are courtesy of the artists and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

About the project’s Kickstarter campaign

Camille Dubois Crôteau is the Communications and Marketing Officer for the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia